- Main

- Biography & Autobiography

- The Feminine Mystique.

The Feminine Mystique.

Betty Friedan你有多喜欢这本书?

下载文件的质量如何?

下载该书,以评价其质量

下载文件的质量如何?

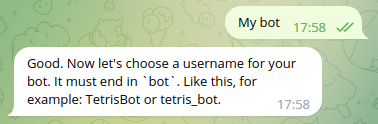

This title presents an analysis of the position of women in Western society. When published in 1963 it met with an enormous response and led to Friedan being called the mother of the new feminist movement.

内容类型:

书籍年:

1977

出版:

2nd Printing

出版社:

Independely Published

语言:

english

页:

420

ISBN 10:

0440124980

ISBN 13:

9780440124986

文件:

PDF, 67.57 MB

您的标签:

IPFS:

CID , CID Blake2b

english, 1977

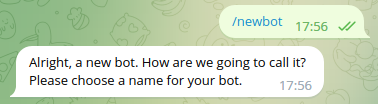

在1-5分钟内,文件将被发送到您的电子邮件。

该文件将通过电报信使发送给您。 您最多可能需要 1-5 分钟才能收到它。

注意:确保您已将您的帐户链接到 Z-Library Telegram 机器人。

该文件将发送到您的 Kindle 帐户。 您最多可能需要 1-5 分钟才能收到它。

请注意:您需要验证要发送到Kindle的每本书。检查您的邮箱中是否有来自亚马逊Kindle的验证电子邮件。

正在转换

转换为 失败

关键词

关联书单

8.

om 018

•

I n6

~~ by~·"

Botty .

Friodan

"THE BOOK WE WERE WAITING FOR . . . THE

WISEST, SANEST, SOUNDEST, MOST UNDERSTAND·

ING AND COMPASSIONATE TREATMENT OF AMERI·

CAN WOMAN'S GREATEST PROBLEM."

-Ashley Montagu

"This is one of those rare books we are

endowed with only once in several decades;

a volume which launches a major social

movement, toward a more humane and

just society. Betty Friedan is a liberator of

women and men."

-Amitai Etzioni,

Chairman, Department of Sociology,

Columbia University

"The most important book of the twentieth

century . . . Betty Friedan is to women

what Martin Luther King was to blacks."

-Barbara Seaman, author of Free and Female

"It states the trouble with women so clearly

that every woman can recognize herself.

. . . Things are different between men and

women because we now have words for the

trouble. Betty gave them to us."

-Caroline Bird, author of

Everything a Woman Needs to Know

to Get Paid What She's Worth

o .

'Fomlnino ,

~tiquo

~

. ·~~by~~· .

Botty

Friodan

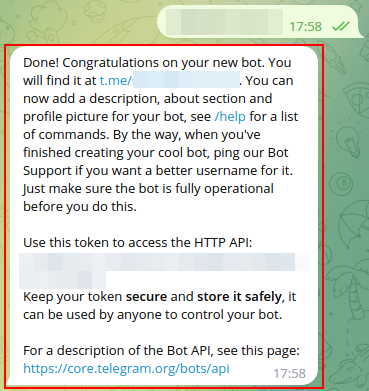

With aNew Introduction and Epilogue

by the Author

A DELL BOOK

~

I:

1'

~.

t

Published by

DELL PUBLISHING CO., INC.

1 Dag Hammarskjold Plaza

New York, New York 10017

Copyright © 1974, 1963 by Betty Friedan

Selections from this book have appeared in

Mademoiselle © 1962 by the Conde Nast Publications, Inc.,

Ladies' Home Journal © 1963 by Betty Friedan and

McCall's © 1963 by Betty Friedan.

Introduction and Epilogue first published in the

New York Times Magazine. Copyright © 1973 by

Betty Friedan.

All rights reserved. For information contact

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

New York, New York 10003

Dell ® TM 681510, Dell Publishing Co., Inc.

IBSN: 0-440-12498-0

Reprinted by arrangement with

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America

Previous Dell Edition #2498

New Dell Edition

First printing-September 1977

Second printing-June 1979

I

I

For all the new women,

and the new men

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

7

ONE

THE PROBLEM THAT HAS NO NAME

11

TWO

THE HAPP; Y HOUSEWIFE HEROINE

28

THREE

THE CRISIS IN WOMAN'S IDENTITY

62

FOUR

THE PASSIONATE JOURNEY

73

FI VE

THE SEXUAL SOLIPSISM

OF SIGMUND FREUD

95

SIX

THE FUNCTIONAL FREEZE,

THE FEMININE PROTEST,

AND MARGARET MEAD

117

SEVEN

THE SEX-DIRECTED EDUCATORS

142"

I,,

f

!

EI GHT

THE MISTAKEN CHOICE

174

N I NE

THE SEXUAL SELL

191

TEN

HOUSEWIFERY EXPANDS TO

FILL THE TIME AVAILABLE

224

ELEVEN

THE SEX-SEEKERS

241

TWELVE

PROGRESSIVE DEHUMANIZATION:

THE COMFORTABLE CONCENTRATION CAMP

271

THIRTEEN

THE FORFEITED SELF

299

FOURTEEN

A NEW LIFE PLAN FOR WOMEN

326

EPILOGUE

365

NOTES

381

INDEX

409

INTRODUCTION

JO THE TENTH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

IT IS A DECADE NOW SINCE THE PUBLICATION OF

The Feminine Mystique, and until I started writing the

book, I wasn't even conscious of the woman problem.

Locked as we all were then in that mystique, which kept

us passive and apart, and kept us from seeing our real

problems and possibilities, I, like other women, thought

there was something wrong with me because I didn't have

an orgasm waxing the kitchen floor. I was a freak, writing

that book-not that I waxed any floor, I must admit, in

the throes of finishing it in 1963.

Each of us thou ht she was a freak ten ears a 0 if she

didn't expenence~~~ ~~ious or~ashc

ment the

Commercials prom;;;ed 3i/h;;; waxing the kitchen floor.

""HOWever much we enjoyed being Junior's and Janey"S or~

Emily's mother, or B.J.'s wife, if we still had amibitions,

ideas about ourselves as people in our own right-well,

we were simply freaks, neurotics, and we confessed our

sin or neurosis to priest or psychoanalyst, and tried hard

to adjust. We didn't admit it to each other if we felt there

should be more In hfe {han eanut-butter sandWIches WIth

e kids,

throwing power In 0

was ng mac ine

didn't make us relive our wedding night, if getting the

socks or shirts pure white was not exactly a peak experience, even if we did feel guilty about the tattletale gray.

Some of us (in 1963, nearly half of all women in the

United States) Were already commIftmg me UnpardObable

SIn of working outside the home to belp pay the mortgage

"or W'0cery tid!. Those who did felt guilty, too-about be~mg their femimmty, yndermining their husbands' masculImty, and neglecting their children by daring to work

for money at all, no matter how much it was needed.

They couldn't admit, even to themselves; that the:ll- resentt:..d being paid half what a man would have been paid for

2

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

the job, or always being passed over for promotion, or

writing the paper for which he got the degree and the

raise.

A suburban neighbor of mine named Gertie was having

coffee with me when the census taker came as I was writing The Feminine Mystique. "Occupation?" the census

taker asked, "Housewife," I said. Gertie, who had cheered

me on in my efforts at writing and seIling magazine articles, shook her head sadly. "You should take yourself

more seriously," she said. I hesitated, and then said to the

census taker, "Actually, I'm a writer." But, of course, I

then was, and still am, like all married women in America, no matter what else we do between 9 and 5, a housewife. Of co se single women di 't

"house. ".

the cens

e came around ut even ere ,

society was less interested in what these women were

~persons in the world than in askmg, "WhY lsn~

'IiiCegiIi like you married.:E And so they: too, were~

~ged to take themselves seriously.

It seems such a precarious accident that I ever wrote

the book at all-but, in another way, my whole life had

prepared me to write that book. All the pieces finally

came together. In 1957, getting strangely bored with writing articles about breast feeding and the like for Redbook

and the Ladies' Home Journal, I put an unconscionable

amount of time into a questionnaire for my fellow Smith

graduates of the class of 1942, thinking I was going

. ove the current notion that education had fitted us ill

for our ro e as women. But t e questionnaire raised more

questions than it answered for me-education had not exactly geared us to the role women he~ng tQ..PW. it

seemed. The suspicion arose as to weer it was the education or the role 'that was wrong. McCall's commissioned

an article based on my Smith alumnae questionnaire, but

the then male publisher of McCall's, during that great era

of togetherness, turned the piece down in horror, despite

underground efforts of female editors. The male McCall's

editors said it couldn't be true.

I was next commissioned to do the article for Ladies'

Home Journal. That time I took it back, because they

rewrote it to say just the opposite of what, in fact, I was

trying to say. I tried it again for Redbook. Each time I

was interviewing more women, psychologists, sociologists,

INTRODUCTION

3

marriage counselors, and the like and getting more and

-more sure I was on the track of something. But what? I

needed a name for whatever it was that kept us from

using our rights, that made us feel guilty about anything

we did not as our husbands' wives, our children's mothers,

but as people ourselves. I needed a name to describe that

guilt. uolike tbe guilt women used to feel about sexual

needs, the guilt they felt now was about needs

. ,

t e sexua e 1 on 0 women, the mystique of feminine fulfillment-the femmme mystique.

"The editor of Redbook told my agent, "Betty has gone

off her rocker. She has always done a good job for us, but

this time only the most neurotic housewife could

identify." I opened my agent's letter on the subway as I

was taking the kids to the pediatrician. I got off the subway to call my agent and told her, "I'll have to write a

book to get this into print." What I Was writing threatened the very foundations of the women's magazIne

World-the feminine mystique.

When Norton contracted for the book, I thought it

would take a year to finish it; it took five. I wouldn't have

even started it if the New York Public Library had not, at

just the right time, opened the Frederick Lewis Allen

Room, where writers working on a book could get a desk,

six months at a time, rent free. I got a baby-sitter three

days a week and took the bus from Rockland County to

the city and somehow managed to prolong the six months

to two years in the Allen Room, enduring much joking

from other writers at lunch when it came out that I was

writing a book about women. Then, somehow, the book

took me over, obsessed me, wanted to write itself, and I

took my papers home and wrote on the dining-room table,

the living-room couch, on a neighbor's dock on the river,

and kept on writing it in my mind when I stopped to take

the kids somewhere or make dinner, and went back to it

after they were in bed.

I have never experienced anything as powerful, truly

mystical, as the forces that seemed to take me over when

I was writing The Feminine Mystique. The book came

from somewhere deep within me and all my experience

came together in it: my mother's discontent, my own

training in Gestalt and Freudian psychology, the fellowship I felt guilty about giving up, the stint as a reporter

4

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

which taught me how to follow clues to the hidden

economic underside of reality, my exodus to the suburbs

and all the hours with other mothers shopping at supermarkets, taking the children swimming, coffee klatches.

Even the years of writing for women's magazines when it

was unquestioned gospel that women could identify with

nothing beyond the home-not politics, not art, not

science, not events large or small, war or peace, in the

United States or the world, unless it could be approached

through female experience as a wife or mother or translated into domestic detail I I could no longer write within

that framework. The book I was now writing challenged

the very definition of that universe-what I chose to call

the feminine mystique. Giving it a name, I knew that it

was not the only possible universe for women at all but an

unnatural confining of our energies and vision. But as I

began following leads and clues from women's words and

my own feelings, across psychology, sociology, and recent

history, tracing back-through the pages of the magazines

for which I'd written-why and how it happened, what it

was really doing to women, to their children, even to sex,

the implications became apparent and they were fantastic.

I was surprised myself at what I was writing, where it was

leading. After I finished each chapter, a part of me would

wonder, Am I crazy? But there was also a growing feeling

of calm, strong, gut-sureness as the clues fitted together,

which must be the same kind of feeling a scientist has

when he or she zeroes in on a discovery in one of those

true-science detective stories.

Qnly this was not just abstract and conceptual. It meant

tpat I and eyery other woman I knew had been hvmg a

lie,

all the doctors who treated us and the experts

WDostudie us were e etuatm

at Ie

ur omesa

sc 00 s an churches and politics and professions

were built around that lie. If women were really peopleno more, no less--then all the things that kept them from

being full people in our society would have to be changed.

And women, once they broke through the feminine mystique and took themselves seriously as people, would see

~the.i; place on a false pedestal, even their glorification as

sexual objects, for the putdown it was.

Yet if I had realized how fantastically fast that would

really happen-already in less than ten years' time--

INTRODUCTION

5

maybe I would have been so scared I might have stopped

writing. It's frightening when you're starting on a new

road that no one has been on before. You don't know

how far it's going to take you until you look back and realize how far, how very far you've gone. When the first

woman asked me, in 1963, to autograph The Feminine

Mystique, saying what by now hundreds-thousands, I

guess--of women have said to me, "It changed my whole

life," I wrote, "Courage to us all on the new road." Because there is no turning back on that road. It has to

change your whole life; it certainly changed mine.

Betty Friedan

New York, 1973

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

GRADUALLY, WITHOUT SEEING IT CLEARLY FOR QUITE

a while, I came to realize that something is very wrong with

the way American women are trying to live their lives today. I sensed it first as a question mark in my own life, as a

wife and mother of three small children, half-guiltily, and

therefore half-heartedly, almost in spite of myself, using

my abilities and education in work that took me away from

home. It was this personal question mark that led me, in

1957, to spend a great deal of time doing an intensive questionnaire of my college classmates, fifteen years after our

graduation from Smith. The answers given by 200 women

to, those intimate open-ended questions made me realize

that what was wrong could not be related to education in

the way it was then believed to be. The problems and satisfaction of their lives, and mine, and the way our education

had contributed to them, simply did not fit the image of

the modern American woman as she was written about in

women's magazines, studied and analyzed in classrooms and

clinics, praised and damned in a ceaseless barrage of words

ever since the end of World War II. There was a strange

discre anc between the real it of our lives as women and

the image to which we were try1Pg to cont rm, e unage

that I came to call the feminine mystique. I wondered if

other women faced this schizophrenic split, and what it

meant.

-And so I began to hunt down the origins of the feminine

mystique, and its effect on women who lived by it, or grew

up under it. My methods were simply those of a reporter

on the trail of a story, except I soon discovered that this

was no ordinary story. For the startling pattern that began

to emerge, as one clue led me to another in far-flung fields

of modern thought and life, defied not only the conventional image but basic psychological assumptions about women.

I found a few pieces of the puzzle in previolls studies of

women: but not many, for women in the past have been

studied in terms of the feminine mystique. The Mellon

study of Vassar women was provocative, SimonITeBean:-

8

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

)ii~g~t(~.trench ~m~.... the work of M!rra--Ko,A. . aslow, Alva Myrdal. I found even more

provocative the growing body of new psychological thought

on the question of man's identity, whose implications for

women seem not to have been realized. I found further

evidence by questioning those who treat women's ills and

problems. And I traced the growth of the mystique by talking to editors of women's magazines, advertising motivational researchers, and theoretical experts on women in the

fields of psychology, psychoanalysis, anthropology, sociology, and family-life education. But the puzzle did not begin

to fit together until I interviewed at some depth, from two

hours to two days each, eighty women at certain crucial

points in their life cycle---high school and college girls facing or evading the question of who they were; young housewives and mothers for whom, if the mystique were right,

there should be no such question and who thus had no

name for the problem troubling them; and women who

faced a jumping-off point at forty. These women, some tortured, some serene, gave me the final clues, and the most

damning indictment of the feminine mystique.

I could not, however, have written this book without the

assistance of many experts, both eminent theoreticians and

practical workers in the field, and, indeed, without the cooperation of many who themselves believe and have helped

perpetrate the feminine mystique. I was helped by many

present and former editors of women's magazines, including Peggy Bell, John English, Bruce Gould, Mary Ann Guitar, James Skardon, Nancy Lynch, Geraldine Rhoads, Robert Stein, Neal Stuart and Polly Weaver; by Ernest Dichter

and the staff of the Institute for Motivational Research; and

by Marion Skedgell, former editor of the Viking Press, who

gave me her data from an unfinished study of fiction heroines. Among behavioral scientists, theoreticians and thera, pists in the field, lowe a great debt to William Menaker

and John Landgraf of New York University, A. H. Maslow

of Brandeis, John Dollard of Yale, William J. Goode of

Columbia; to Margaret Mead; to Paul Vahamian of Teachers College, Elsa Siipola Israel and Eli Chinoy of Smith.

And to Dr. Andras Angyal, psychoanalyst of Boston, Dr.

Nathan Ackerman of New York, Dr. Louis English and Dr.

Margaret Lawrence of the Rockland County Mental Health

Center; to many mental health workers in Westchester

County, including Mrs. Emily Gould, Dr. Gerald Fountain,

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

9

Dr. Henrietta Glatzer and Marjorie Ilgenfritz of the Guidance Center of New Rochelle and the Rev. Edgar Jackson;

Dr. Richard Gordon and Katherine Gordon of Bergen

County, New Jersey; the late Dr. Abraham Stone, Dr. Lena

Levine and Fred Jaffe of the Planned Parenthood Association, the staff of the James Jackson Putnam Center in Boston, Dr. Doris Menzer and Dr. Somers Sturges of the Peter

Bent Brigham Hospital, Alice King of the Alumnae Advisory Center and Dr. Lester Evans of the Commonwealth

Fund. I am also grateful to those educators valiantly fighting the feminine mystique, who gave me helpful insights:

Laura Bornholdt of Wellesley, Mary Bunting of Radcliffe,

Marjorie Nicolson of Columbia, Esther Lloyd-Jones of

Teachers College, Millicent McIntosh of Barnard, Esther

Raushenbush of Sarah Lawrence, Thomas, Mendenhall of

Smith, Daniel Aaron and many other members of the

Smith faculty. I am above all grateful to the women who

shared their problems and feelings with me, beginning with

200 women of Smith, 1942, and Marion Ingersoll Howell

and Anne Mather Montero, who worked with me on the

alumnae questionnaire that started my search.

Without that superb institution, the Frederick Lewis Allen Room of the New York Public Library and its provision

to a writer of quiet work space and continuous access to

research sources, this particular mother of three might never have started a book, much less finished it. The same

might be said of the sensitive support of my publisher,

George P. Brockway, and my editor, Burton Beals, of

W. W. Norton & Company. In a larger sense, this book

might never have been written if I had not had a most unusual education in psychology, from Kurt KoiIka, Harold

Israel, Elsa Siipola and James Gibson at Smith; from Kurt

Lewin, Tamara Dembo, and the others of their group then

at Iowa; and from E. C. Tolman, Jean Macfarlane, Nevitt

Sanford and Erik Erikson at Berkeley-a liberal education,

in the best sense, which was meant to be used, though I

have not used it as I originally planned.

The insights, interpretations both of theory and fact, and

the implicit values of this book are inevitably my own. But

whether or not the answers I present here are final-and

there are many questions which social scientists must probe

further-the dilemma of the American woman is real. At

the present time, many experts, finally forced to recognize

this problem, are redoubling their efforts to adjust women

,-I

10

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

to it in terms of the feminine mystique. My answers may

disturb the experts and women alike, for they imply social

change. But there would be no sense in my writing this book

at all if I did not believe that women can affect society, as

well as be affected by it; that, in the end, a woman, as a

man, has the power to choose, and to make her own heaven

or hell.

Grandview, New York

June 1957-July 1962

ONE

THE PROBLEM THAT HAS NO NAME

THE PROBLEM LAY BURIED, UNSPOKEN, FOR MANY

years in the minds of American women. It was a strange

stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women

suffered in the middle of the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As

she made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children,

chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night-she was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question-HIs this all?"

For over fifteen years there was no word of this yearning in the millions of words written about women, for women, in all the columns, books and articles by experts telling

women their role was to seek fulfillment as wives and

mothers. Over and over women heard in voices of tradition

and of Freudian sophistication that they could desire no

greater destiny than to glory in their own femininity. Experts told them how to catch a man and keep him, how to

breast feed children and handle their toilet training, how to

cope with sibling rivalry and adolescent rebellion; how to

buy a dishwasher, bake bread, cook gourmet snails, and

build a swimming pool with their own hands; how to dress,

look, and act more feminine and make marriage more exciting; how to keep their husbands from dying young and

their sons from growing into delinquents. They were taught

to pity the neurotic, unfeminine, unhappy women who

wanted to be poets or physicists or presidents. They learned

that truly feminine women do not want careers, higher education, political rights-the independence and the opportunities that the old-fashioned feminists fought for. Some

women, in their forties and fifties, still remembered painfully giving up those dreams, but most of the younger women no longer even thought about them. A thousand expert

voices applauded their femininity, their adjustment, their

new maturity. All they had to do was devote their lives

12

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

from earliest girlhood to finding a husband and bearing

children.

By the end of th~ nineteen-fifties, the average marriage

age of women in America dropped to 20, and was still

dropping, into the teens. Fourteen million girls were engaged by 17. The proportion of women attending college in

comparison with men dtoppmg from 47 per cent m 1910t0

35 per cent in 1958. A century e~~ir, ~p. bad fougbt

im'1ii her educatIOn; now iris wen 0 co Ie e to t husban. y e mid-fifties, 60 per cent droppe out of college

ro-marry, or oecau:se they were afraid too much educatIon

-w6lIlObe a marriage bar. Colleges built dormitories for

"married students," but the students were almost always

the husbands. 4.yew degree was instituted for the wives·~Ph.T." (putting Husband Through).

Then American girls began ge~ married in high school.

And the women's magazines, deploring the unhappy statistics about these young marriages, urged that courses on

marriage, and marriage counselors, be installed in the high

schools. Girls started going steady at twelve and thirteen,

in junior high. Manufacturers put out brassieres with false

bosoms of foam rubber for little girls of ten. And an advertisement for a child's dress, sizes 3-6x, in the New York

Times in the fall of 1960, said: "She Too Can Join the

Man-Trap Set."

By the end of the fifties, the United States birthrate was

overtaking India's. The birth-control movement, renamed

Planned Parenthood, was asked to find a method whereby

women who had been advised that a third or fourth baby

would be born dead or defective might have it anyhow.

Statisticians were especially astounded at the fantastic increase in the number of babies among college women.

Where once they had two children, now they had four,

five, six. Women who had once wanted careers were now

making careers out of having babies. So rejoiced Lite magazine in a 1956 paean to the movement of American women back to the home.

In a New York hospital, a woman had a nervous breakdown when she found she could not breast feed her baby.

J-o-o.tll~ hospitals. women d~of cancer refused a.--drug

which research had provedl!!ight save their li~: i1S_ side

[ffects were said to be unfeminine~ "If I have only one life,

-letri,e live it as a blonde," a larger-than-life-sized picture of

a pretty, vacuous woman proclaimed from newspaper,

THE PROBLEM THAT HAS NO NAME

13

magazine, and drugstore ads. And across America, three

out of every ten women dyed their hair blonde. They ate a

chalk called Metrecal, instead of food, to shrink to the size

of the thin young models. Department-store buyers reported that American women, since 1939, had become three

and four sizes smaller. "Women are out to fit the clothes,

instead of vice-versa," one buyer said.

Interior decorators were designing kitchens with mosaic

murals and original paintings, for kitchens were once again

the center of women's lives. Home sewing became a

million-dolIar industry. Many women no longer left their

homes, except to shop, chauffeur their children, or attend

a social engagement with their husbands. Girls were growing up in America without ever having jobs outside the

home. In the late fifties, a sociological phenomenon was

suddenly remarked: a third of American women now

worked, but most were no longer young and very few were

pursuing careers. They were married women who held parttime jobs, selling or secretarial, to put their husbands

through school, their sons through college, or to help pay

the mortgage. Or they were widows supporting families.

Fewer and fewer women were entering professional work.

The shortages in the nursing, social work, and teaching professions caused crises in almost every American city. Concerned over the Soviet Union's lead in the space race,

scientists noted that America's greatest source of unused

frain-power was women. But girls would not stud¥- ph¥sics:

it was "unfeminine." A girl r\!fused a science fellowship at

Johns Hopkins to take a job in a real-estate office. All she

wanted, she said, was what every other American girl wanted-to get married, have four children and live in a nice

house in a nice suburb.

The suburban housewife-she was the dream ~~e of

thCyoung AmerIcan women and the e

it waF i 0i

women

over the world. The American housewife--freed

bY sCIence and labor-saving appliances from the drudgery,

the dangers of childbirth and the illnesses of her grandmother. She was healthy, beautiful, educated. concerned

o.!}ly about her husfiilid, her chjldren , her home. She had

found true feminine fulfillment. As a housewife and mothe;,~ respected as a full and equal partner to man in

his world. She w~s free to choose automohiles. clothes,~p

pliances, supermarkets; she had everything that womeD ever dreamed of.

14

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

In the fifteen years after World War II, this mystique of

feminine fulfillment became the cherished and self-perpetuating core of contemporary American culture. Millions of

women lived their lives in the image of those pretty pictures

of the American suburban housewife, kissing their husbands

goodbye in front of the picture window, depositing their

stationwagonsful of children at school, and smiling as they

ran the new electric waxer over the spotless kitchen floor.

They- baked their own bread, sewed their own and their

children's clothes, kept their new washing machines and

dryers running all day. They changed the sheets on the beds

twice a week instead of once, took the rug-hooking class in

adult education" and pitied their poor frustrated mothers,

who had dreamed of having a career. Their only dream

was to be perfect wives and mothers; their highest ambition to have five children and a beautiful house, their only

fight to get and keep their husbands. They had no thought

for the unfeminine problems of the world outside the home;

they wanted the men to make the major decisions. They

gloried in their role as women, and wrote proudly on the

census blank: "Occupation: housewife."

For over fifteen years, the words written for women,

and the words women used when they talked to each other,

while their husbands sat on the other side of the room and

talked shop or politics or septic tanks, were about problems with their children, or how to keep their husbands

happy, or imp,rove their children's school, or cook chicken

or make slipcovers. Nobody argued whether women were

inferior or superior to men; they were simply different.

Words like "emancipation" and "career" sounded strange

and embarrassing; no one had used them for years. When

a Frenchwoman named Simone de Beauvoir wrote a book

called The Second Sex, an American critic commented that

she obviously "didn't know what life was all about," and

besides, she was talking about French women. The "woman

problem" in America no longer existed.

If a woman had a problem in the 1950's and 1960's, she

knew that something must be wrong with her marriage, or

with herself. Other women were satisfied with their lives,

she thought. Whal kind of a woman was she if she did not

feel this mysterious fulfillment waxing the kitchen floor?

She was so ashamed to admit her dissatisfaction that she

never knew how many other women shared it. If she tried

to tell her husband, he didn't understand what she was talk-

THE PROBLEM THAT HAS NO NAME

15

ing about. She did not really understand it herself. For over

fifteen years women in America found it harder to talk

about this problem than about sex. Even the psychoanalysts had no name for it. When a woman went to a psychiatrist for help, as many women did, she would say,

"I'm so ashamed," or "I must be hopelessly neurotic." "I

don't know what's wrong with women today," a suburban

psychiatrist said uneasily. "I only know something is wrong

because most of my patients happen to be women. And

their problem isn't sexual." Most women with this problem

did not go to see a psychoanalyst, however. "There's nothing wrong really," they kept telling themselves. "There isn't

any problem."

But on an April morning in 1959, I heard a mother of

four, having coffee with four other mothers in a suburban

development fifteen miles from New York, say in a tone

of quiet desperation, "the problem." And the others knew,

without words, that she was not talking about a problem

with her husband, or her children, or her home. Suddenly

they realized they all shared the same problem, the problem that has no name. They began, hesitantly, to talk about

it. Later, after they had picked up their children at nursery

school and taken them home to nap, two of the women

cried, in sheer relief, just to know they were not alone.

Gradually I came to realize that the problem that has no

name was shared by countless women in America. As a

magazine writer I often interviewed women about problems with their children, or their marriages, or their houses,

or their communities. But after a while I began to recognize the telltale signs of this other problem. I saw the same

signs in suburban ranch houses and split-levels on Long Island and in New Jersey and Westchester County; in colonial houses in a small Massachusetts town; on patios in

Memphis; in suburban and city apartments; in living rooms

in the Midwest. Sometimes I sensed the problem, not as a

reporter, but as a suburban housewife, for during this time

I was also bringing up my own three children in Rockland

County, New York. I heard echoes of the problem in college dormitories and semi-private maternity wards, at PTA

meetings and luncheons of the League of W omen Voters,

at suburban cocktail parties, in station wagons waiting for

trains, and in snatches of conversation overheard at

Schrafft's. The groping words I heard from other women,

16

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

on quiet afternoons when children were at school or on

quiet evenings when husbands worked late, I think I understood first as a woman long before I understood their larger social and psychological implications.

Just what was this problem that has no name? What

were the words women used when they tried to express it?

Sometimes a woman would say "I feel empty somehow

. . . incomplete." Or she would say, "I feel as if I don't

exist." Sometimes she blotted out the feeling with a tranquilizer. Sometimes she thought the problem was with her

husband, or her children, or that what she really needed

was to redecorate her house, or move to a better neighborhood, or have an affair, or another baby. Sometimes,

she went to a doctor with symptoms she could hardly describe: "A tired feeling . . . I get so angry with the children it scares me . . . I feel like crying without any reason." (A Cleveland doctor called it "the housewife's

syndrome.") A number of women told me about great

bleeding blisters that break out on their hands and arms. "I .

call it the housewife's blight," said a family doctor in Pennsylvania. "I see it so often lately in these young women with

four, five and six children who bury themselves in their

dishpans. But it isn't caused by detergent and it isn't cured

by cortisone."

Sometimes a woman would tell me that the feeling gets

so strong she runs out of the house and walks through the

streets. Or she stays inside her house and cries. Or her children tell her a joke, and she doesn't laugh because she

doesn't hear it. I talked to women who had spent years on

the analyst's couch, working out their "adjustment to the

feminine role," their blocks to "fulfilJment as a wife and

mother." But the desperate tone in these women's voices,

and the look in their eyes, was the same as the tone and the

look of other women, who were sure they had no problem,

even though they did have a strange feeling of desperation.

A mother of four who left college at nineteen to get married told me:

I've tried everything women are supposed to do--hobhies, gardening, pickling, canning, being very social with

my neighbors, joining committees, running PTA teas. I

can do it all, and I like it, but it doesn't leave you anything to think about-any feeling of who you are. I never

had any career ambitions. All I wanted was to get mar-

THE PROB.LEM THAT HAS NO NAME

17

ried and have four children. I love the kids and Bob and

my home. There's no problem you can even put a name

to. But I'm desperate. I begin to feel I have no personality. I'm a server of food and putter-on of pants and a

bedmaker, somebody who can be called on when you

want something. But who am I?

A twenty-three-year-old mother in blue jeans said:

I ask myself why I'm so dissatisfied. I've got my

health, fine children, a lovely new home, enough money.

My husband has a real future as an electronics engineer.

He doesn't have any of these feelings. He says maybe I

need a vacation, let's go to New York for a weekend.

But that isn't it. I always had this idea we should do

everything together. I can't sit down and read a book

alone. If the children are napping and I have one hour to

myself I just walk through the house waiting for them to

wake up. I don't make a move until I know where the

rest of the crowd is going. It's as if ever since you were

a little girl, there's always been somebody or something

that will take care of your life: your parents, or coIlege,

or falling in love, or having a child, or moving to a new

house. Then you wake up one morning and there's nothing to look forward to.

A young wife in a Long Island development said:

I seem to sleep so much. I don't know why I should be

so tired. This house isn't nearly so hard to clean as the

cold-water flat we had when I was working. The children

are at school all day. It's not the work. I just don't feel

alive.

In 1960, the problem that has no name burst like a boil

through the image of the happy American housewife. In the

television commercials the pretty housewives still beamed

over their foaming dishpans and Time's cover story on ''The

Suburban Wife, an American Phenomenon" protested:

"Having too good a time . . . to believe that they should

be unhappy." But the actual unhappiness of the American

housewife was suddenly being reported-from the New

York Times and Newsweek to Good Housekeeping and

CBS Television ("The Trapped Housewife"), although al-

18

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

most everybody who talked about it found some superficial

reason to dismiss it. It was attributed to incompetent appliance repairmen (New York Times), or the distances

children must be chauffeured in the suburbs (Time), or too

much PTA (Redbook). Some said it was the old problem

-education: more and rii6r'e"';omen a e ucatlOn

c

~ rna e t em u

a

III t elf ro e as housewives.

"The road from reud to Frigidaire, from op oc es 0

Spock, has turned out to be a bumpy one," reported the

New York Times (June 28, 1960). "Many young women

--certainly not all-whose education plunged them into a

world of ideas feel stifled in their homes. They find their

routine lives out of joint with their training. Like shut-ins,

they feel left out. In the last year, the problem of the educated housewife has provided the meat of dozens of

speeches made by troubled presidents of women's colleges

who maintain, in the face of complaints, that sixteen years

of academic training is realistic preparation for wifehood

and motherhood."

There was much sympathy for the educated housewife.

("Like a two-headed schizophrenic . . . once she wrote a

paper on the Graveyard poets; now she writes notes to the

milkman. Once she determined the boiling point of sulphuric acid; now she determines her boiling point with the overdue repairman. . . . The housewife often is reduced to

screams and tears. . . . No one, it seems, is appreciative,

least of all herself, of the kind of person she becomes in

the process of turning from poetess into shrew.")

Home economists suggested more realistic preparation

for housewives, such as high-school workshops in home

appliances. College educators suggested more discussion

groups on home management and the family, to prepare

women for the adjustment to domestic life. A spate of articles appeared in the mass magazines offering "Fifty-eight

Ways to Make Your Marriage More Exciting." No month

went by without a new book by a psychiatrist or sexologist

offering technical advice on finding greater fulfillment

through sex.

A male humorist joked in Harper's Bazaar (July, 1960)

that the problem could be solved by taking away woman's

right to vote. ("In the pre-19th Amendment era, the American woman was placid, sheltered and sure of her role in

American society. She left all the political decisions to her

THE PROBLEM THAT HAS NO NAME

19

husband and be, in turn, left all the family decisions to her.

Today a woman bas to make both the family and the political decisions, and it's too much for ber.")

A number of educators suggested seriously that women

no longer be admitted to the four-year colleges and universities: in the growing college crisis, the education which

girls could not use as housewives was more urgently needed than ever by boys to do the work of the atomic age.

The problem was also dismissed with drastic solutions

no one could take seriously. (A woman writer proposed in

Harper's that women be drafted for compulsory service as

nurses' aides and baby-sitters.) And it was smootbed over

with the age-old panaceas: "love is their answer," "the only

answer is inner help," "the secret of completeness--children," "a private means of intellectual fulfillment," "to

cure this toothache of the spirit-the simple formula of

banding one's self and one's will over to God."l

lem was dismissed by telling the housewife she

doesn't realize how uc

s e 1S- er own oss, no

'£Iock, no junior executive gunnmg or er JO.

at 1 s e

isn't happy-does she think men are happy in this world?

Does she really, secretly, still want to be a man? Doesn't

she know yet how lucky she is to be a woman?

The problem was also, and finally, dismissed by shrugging that there are no solutions: this is what being a woman

means, and what is wrong with American women that they

can't accept their role gracefully? As Newsweek put it

(March 7, 1960):

She is dissatisfied with a lot that women of other lands

can only dream of. Her discontent is deep, pervasive,

and impervious to the superficial remedies which are offered at every hand. . . . An army of professional explorers have already charted the major sources of trouble. . . . From the beginning of time, the female cycle

has defined and confined woman's role. As ~ was

credited with saying: "Anatomy isdestiBY." 1tlough no

group of women has ever pushed these natural restrictions as far as the American wife, it seems that she still

cannot accept them with good grace, . . . A young

mother with a beautiful family, charm, talent and brains

is apt to dismiss her role apologetically. "What do I do?"

you hear her say. "Why nothing. I'm just a housewife."

20

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

A good education, it seems, has given this paragon among

women an understanding of the value of everything except her own worth . . .

And so she must accept the fact that "American women's unhappmess IS merely the most recentl won of womn s fig ts, an

JUS an

say WIt the happy housewife

'-fOund 5y Newsweek: "We ought to salute the wonderful

freedom we all have and be proud of our lives today. I

have had college and I've worked, but being a housewife is

the most rewarding and satisfying role. . . . My mother

was never included in my father's business affairs . . . she

couldn't get out of the house and away from us children.

But I am an equal to my husband; I can go along with him

on business trips and to social business affairs."

The alternative offered was a choice that few women

would contemplate. In the sympathetic words of the New

York Times: "All admit to being deeply frustrated at times

by the lack of privacy, the physical burden, the routine of

family life, the confinement of it. However, none would

give up her home and family if she had the choice to make

again." Redbook commented: "Few women would want to

thumb their noses at husbands, children and community

and go off on their own. Those who do may be talented individuals, but they rarely are successful women."

The year American women's discontent boiled over, it

was also reported (Look) that the more than 21,000,000

American women who are single, widowed, or divorced do

not cease even after fifty their frenzied, desperate search

for a man, And the search begins early-for seventy per

cent of all American women now marry before they are

twenty-four, A pretty twenty-five-year-old secretary took

thirty-five different jobs in six months in the futile hope of

finding a husband, Wom'en were moving from one political

club to another, taking evening courses in accounting or

sailing, learning to play golf or ski, joining a number of

churches in succession, going to bars alone, in their ceaseless search for a man.

Of the growing thousands of women currently getting private psychiatric help in the United States, the married ones

were reported dissatisfied with their marriages, the unmarried ones suffering from anxiety and, finally, depression,

Strangely, a number of psychiatrists stated that, in their experience, unmarried women patients were happier than

THE PROBLEM THAT HAS NO NAME

21

married ones. So the door of all those pretty suburban

houses opened a crack to permit a glimpse of uncounted

thousands of American housewives who suffered alone

from a problem that suddenly everyone was talking about,

and beginning to take for granted, as one of those unreal

problems in American life that can never be solved-like

the hydrogen bomb. By 1962 the plight of the trapped

American housewife had become a national parlor game.

Whole issues of magazines, newspaper columns, books

learned and frivolous, educational conferences and television panels were devoted to the problem.

Even so, most men, and some women, still did not know

that this problem was real. But those who had faced it

honestly knew that all the superficial remedies, the sympathetic advice, the scolding words and the cheering words

were somehow drowning the problem in unreality. A bitter

laugh was beginning to be heard from American women.

They were admired, envied, pitied, theorized over until

they were sick of it, offered drastic solutions or silly choices

that no one could take seriously. They got all kinds of advice from the growing armies of marriage and child-guidance counselors, psychotherapists, and armchair psychologists, on how to adjust to their role as housewives. No other

road to fulfillment was offered to American women in the

middle of the twentieth century. Most adjusted to their role

and suffered or i 0

e roblem that has 0

can e ess painful for a woman, not to hear the strange,

.'fiissatisfied voice stirring withIn her.

It is no longer possible to ignore that voice, to dismiss the

desperation of so many American women. This is not what

being a woman means, no matter what the experts say. For

human suffering there is a reason; perhaps the reason has

not been found because the right questions have not been

asked, or pressed far enough. I do not accept the answer

that there is no problem because American women have

luxuries that women in other times and lands never

dreamed of; part of the strange newness of the problem is

that it cannot be understood in terms of the age-old material problems of man: poverty, sickness, hunger, cold.

The women who suffer this problem have a hunger that

food cannot fill. It persists in women whose husbands are

struggling internes and law clerks, or prosperous doctors and

lawyers; in wives of workers and executives who make

22

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

$5,000 a year or $50,000. It is not caused by lack of material advantages; it may not even be felt by women preoccupied with desperate problems of hunger, poverty or illness. And women who think it will be solved by more

money, a bigger house, a second car, moving to a better

suburb, often discover it gets worse.

lt is no longer possible today to blameJluL.p.rab.lenL.Oll

~@JliAiRity·...tu]iy that edu~Qll_aruUndep.endence

~ali!y with men have mad~ American womelW.lD.:o

'1eminigi. I have heard so many women try to deny this

dissatisfied voice within themselves because it does not fit

the pretty picture of femininity the experts have given

them. I think, in fact, that this is the first clue to the mystery: the problem cannot be understood in the generally

accepted terms by which scientists have studied women,

doctors have treated them, counselors have advised them,

and writers have written about them. Women who suffer

this problem, in whom this voice is stirring, have lived their

whole lives in the pursuit of feminine fulfillment. They are

not career women (although career women may have other problems); they are women whose greatest ambition has

been marriage and children. For the oldest of these women,

these daughters of the American middle class, no other

dream was possible. The ones in their forties and fifties

who once had other dreams gave them up and threw themselves joyously into life as housewives. For the youngest,

the new wives and mothers, this was the only dream. They

are the ones who quit high school and college to marry, or

marked time in some job in which they had no real interest

until they married. These women are very "feminine" in

the usual sense, and yet they still suffer the problem.

Are the women who finished college, the women who

once had dreams beyond housewifery, the ones who suffer

the most? According to the experts they are, but listen to

these four women:

My days are all busy, and dull, too. All I ever do is

mess around. I get up at eight-I make breakfast, so I

do the dishes, have lunch, do some more dishes, and some

laundry and cleaning in the afternoon. Then it's supper

dishes and I get to sit down a few minutes, before the

children have to be sent to bed . . . . That's all there is

to my day. It's just like any other wife's day. Humdrum.

The biggest time, I am chasing kids.

THE PROBLEM THAT HAS NO NAME

23

Ye Gods, what do I do with my time? Well, I get up at

six. I get my son dressed and then give him breakfast.

After that I wash dishes and bathe and feed the baby.

Then I get lunch and while the children nap, I sew or

mend or iron and do all the other things I can't get done

before noon. Then I cook supper for the family and my

husband watches TV while I do the dishes. After I get

the children to bed, I set my hair and then I go to bed.

The problem is always being the children's mommy, or

the minister's wife and never being myself.

A film made of any typical morning in my house

would look like an old Marx Brothers' comedy. I wash

the dishes, rush the older children off to school, dash out

in the yard to cultivate the chrysanthemums, run back

in to make a phone call about a committee meeting, help

the youngest child build a blockhouse, spend fifteen minutes skimming the newspapers so I can be w.ell-informed,

then scamper down to the washing machines where my

thrice-weekly laundry includes enough clothes to keep a

primitive village going for an entire year. By noon I'm

ready for a padded cell. Very little of what I've done

has been really necessary or important. Outside pressures

lash me through the day. Yet I look upon myself as one

of the more relaxed housewives in the neighborhood.

Many of my friends are even more frantic. In the past

sixty years we have come full circle and the American

housewife is once again trapped in a squirrel cage. If the

cage is now a modern plate-glass-and-broadloom ranch

house or a convenient modern apartment, the situation

is no less painful than when her grandmother sat over an

embroidery hoop in her gilt-and-plush parlor and muttered angrily about women's rights.

The first two women never went to college. They live in

developments in Levittown, New Jersey, and Tacoma,

Washington, and were interviewed by a team of sociologists

studying workingmen's wives. 2 The third, a minister's wife,

wrote on the fifteenth reunion questionnaire of her college that she never had any career ambitions, but wishes

now she had. s The fourth, who has a Ph.D. in anthropology, is today a Nebraska housewife with three children. 40

24

THE FEMININE MYSTIQUE

Their words seem to indicate that housewives of all educational levels suffer the same feeling of desperation.

The fact is that no one today is muttering angrily about

"women's rights," even though more and more women have

gone to college. In a recent study of all the classes that have

graduated from Barnard College,5 a significant minority of

earlier graduates blamed their education for making them

want "rights," later classes blamed their education for giving them career dreams, but recent graduates blamed the

c.ollege for making them feel it was not enough simply to

be a housewife and mother; they did not want to feel guilty

if they did not read books or take part in community activities. But if education is not the cause of the problem, the

fact that education somehow festers in these women may

be a clue.

If the secret of feminine fulfillment is having children,

never have so many women, with the freedom to choose,

had so many children, in so few years, so wiJIingly. If the

answer is love, never have women searched for love with

such determination. And yet there is a growing suspicion

that the problem may not be sexual, though it must somehow be related to sex. I have heard from many doctors

evidence of new sexual problems between man and wifesexual hunger in wives so ~eat their husbands cannot satisfy i Amazon

Amazon  Barnes & Noble

Barnes & Noble  Bookshop.org

Bookshop.org  转换文件

转换文件 更多搜索结果

更多搜索结果 其他特权

其他特权