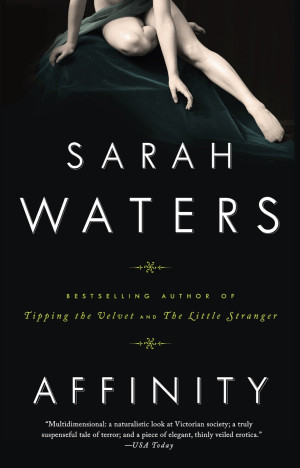

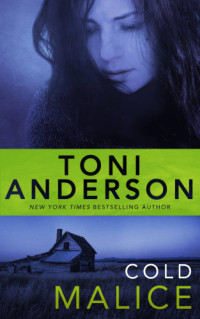

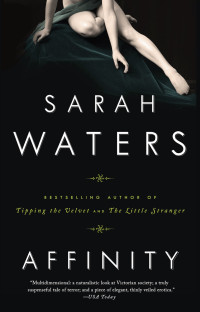

Affinity

Waters Sarah你有多喜欢这本书?

下载文件的质量如何?

下载该书,以评价其质量

下载文件的质量如何?

种类:

内容类型:

书籍年:

2014

出版社:

Penguin Publishing Group

语言:

english

ISBN 10:

1101053119

ISBN 13:

9781101053119

文件:

EPUB, 2.37 MB

您的标签:

IPFS:

CID , CID Blake2b

english, 2014

添加到我的图书馆

- Favorites

在1-5分钟内,文件将被发送到您的电子邮件。

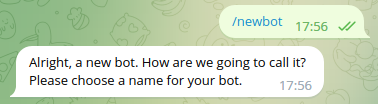

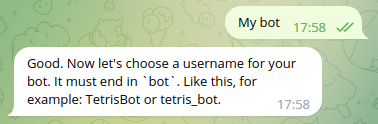

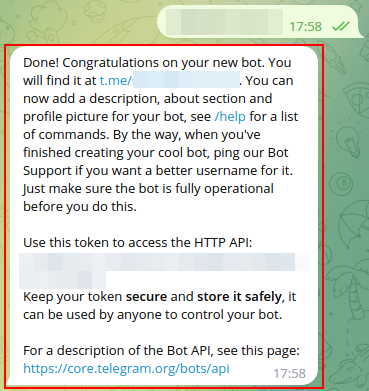

该文件将通过电报信使发送给您。 您最多可能需要 1-5 分钟才能收到它。

注意:确保您已将您的帐户链接到 Z-Library Telegram 机器人。

该文件将发送到您的 Kindle 帐户。 您最多可能需要 1-5 分钟才能收到它。

请注意:您需要验证要发送到Kindle的每本书。检查您的邮箱中是否有来自亚马逊Kindle的验证电子邮件。

正在转换

转换为 失败

关键词

关联书单

Table of Contents Title Page Copyright Page Dedication Part One 24 September 1874 2 September 1872 30 September 1874 30 September 1872 4 October 1872 2 October 1874 6 October 1874 12 October 1872 15 October 1874 16 October 1874 3 November 1872 6 November 1872 13 November 1872 17 November 1872 17 October 1874 25 November 1872 21 October 1874 26 November 1872 Part Two 23 October 1874 9 December 1872 28 October 1874 17 December 1872 19 December 1872 8 January 1873 2 November 1874 25 January 1873 26 January 1873 Part Three 5 November 1874 10 November 1874 14 November 1874 20 November 1874 10 March 1873 21 November 1874 23 November 1874 24 November 1874 2 April 1873 28 November 1874 2 December 1874 26 May 1873 11 December 1874 30 May 1873 Part Four 21 December 1874 23 December 1874 24 December 1874 6 January 1875 14 June 1873 21 June 1873 25 June 1873 3 July 1873 15 January 1875 16 January 1875 19 January 1875 20 January 1875 Part Five 21 January 1875 18 July 1873 1 August 1873 Acknowledgements Also by Sarah Waters Tipping the Velvet This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. RIVERHEAD BOOKS a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. 375 Hudson Street New York, NY 10014 Copyright © 1999 by Sarah Waters. All rights reserved. This book, or parts thereof, may not be reproduced in any form without permission. Published simultaneously in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Waters, Sarah, date. Affinity / by Sarah Waters. p. cm. ISBN: 9781101053119 1. Millbank Penitentiary (London, England)—History—19th century—Fiction. 2. Women prisoners—England—London— Fiction. 3. London (England)—Fiction. I. Title. PR6073.A828 A-087554 823’.914—dc21 This ; book is printed on acid-free paper. Version_2 To Caroline Halliday 3 August 1873 I was never so frightened as I am now. They have left me sitting in the dark, with only the light from the window to write by. They have put me in my own room, they have locked the door on me. They wanted Ruth to do it, but she would not. She said ‘What, do you want me to lock up my own mistress, who has done nothing?’ In the end the doctor took the key from her & locked the door himself, then made her leave me. Now the house is full of voices, all saying my name. If I close my eyes & listen it might be any ordinary night. I might be waiting for Mrs Brink to come & take me down to a dark circle, & Madeleine or any girl might be there, blushing, thinking of Peter, of Peter’s great dark whiskers & shining hands. But Mrs Brink is lying quite alone in her own cold bed, & Madeleine Silvester is downstairs weeping in a fit. And Peter Quick is gone, I think for ever. He was too rough, & Madeleine too nervous. When I told her I could feel him near she only shook & kept her eyes shut. I said ‘It is only Peter. You are not frightened are you, of him? Look, here he is, look at him, open your eyes.’ But she would not do that, she only said ‘O, I am terribly afraid! O Miss Dawes, please don’t have him come any closer!’ Well, many ladies have said that, having Peter come near them for the first time, alone. When he heard her he gave a great laugh. ‘What’s this?’ he said. ‘Am I to come all this way, only to be sent back again? Do you know how hard my journey is & how much I have suffered, & all for your sake?’ Then Madeleine began to cry - of course, some do cry. I said ‘Peter, you must be kinder, Madeleine is only afraid. Be a little gentler & she will let you come close to her, I am sure.’ But when he did step gently to put his hand on her, she gave a scream & grew at once very stiff & white. Then Peter said ‘What’s this, you silly girl? You are spoiling it all. Do you want to be made better or not?’ But she only screamed again, & then she fell, she fell upon the floor & began to kick. I never saw a lady do that. I said ‘My God, Peter!’ & he looked once at me then said ‘Now you little bitch’, & he caught her legs & I put my hands across her mouth. I did it only to make her be quiet & stop jerking, but when I took my hands away there was blood upon them, I think she must have bitten her own tongue or made her nose bleed. I did not even know it for blood at first, it looked so black, & seemed so warm & thick, like sealing-wax. And even with the blood in her mouth she shrieked, until finally the row brought Mrs Brink, I heard her footsteps in the hall & then her voice, that was frightened. She called ‘Miss Dawes, what is it, are you injured, are you hurt?’ & when Madeleine heard that she gave a twist, then cried out clear as anything ‘Mrs Brink, Mrs Brink, they are trying to murder me!’ Then Peter leaned & hit her on her cheek, & after that she lay very quiet & still. Then I thought we really might have killed her. I said ‘Peter, what have you done? Go back! You must go back.’ But as he stepped to the cabinet there came a rattling at the handle of the door & Mrs Brink was there, she had brought her own key with her & had opened the door with that. She was holding a lamp. I said ‘Close the door, here is Peter look & the light is hurting him!’ But she said only ‘What has happened? What have you done?’ She looked at Madeleine lying stiff upon the parlour floor with all her red hair about her, & then at me in my torn petticoat, & then at the blood upon my hands, which was not black now but scarlet. Then she looked at Peter. He had his hands before his face & was crying ‘Take the light away!’ But his gown was open & his white legs showed, & Mrs Brink would not take the lamp away until at last it began to shake. Then she cried ‘O!’ & she looked at me again, & at Madeleine again, & she put her hand upon her heart. She said ‘Not her, too?’ & then ‘O Mamma, Mamma!’ Then she laid the lamp aside & turned her face against the wall, & when I went to her she put her fingers upon my bosom & pushed me from her. I looked once for Peter then, but he had gone. There was only the curtain, dark & shivering, & marked with a mark of silver from his hand. And after all, it is Mrs Brink that has died, not Madeleine. Madeleine had only fainted, & when her maid got her dressed she took her to another room & I heard her walking about & crying there. But Mrs Brink grew weaker & weaker, until finally she could not stand at all. Then Ruth came running, calling ‘What is the matter?’, & she made her lie upon the parlour sofa, all the time pressing her hand & saying ‘You will soon be well, I am sure of it. Look, here am I, & here is Miss Dawes, that love you.’ I thought that Mrs Brink looked then as if she longed to speak but could not, & when Ruth saw that she said we must send out for a doctor. Then she stayed holding tight to Mrs Brink’s hand while he examined her, weeping & saying she would not let it go. Mrs Brink died soon after. She never said another word, Ruth said, except to call again for her mamma. The doctor said that dying ladies very often do become like children. He said her heart was very swollen & must always have been weak, he thought it a wonder she had lived so long as this. He might have gone then, & not thought to ask what startled her, but Mrs Silvester came while he was here & she made him go & look at Madeleine. Madeleine has marks upon her, & when the doctor saw those his voice grew quiet & he said this was a queerer business than he thought. Mrs Silvester said then, ‘Queer? I should say it is criminal!’ She has made a policeman come, it is for that reason they have locked me in my room, the policeman is asking Madeleine who hurt her. She is saying Peter Quick did it, & the gentlemen are answering ‘Peter Quick? Peter Quick? What are you thinking of?’ There isn’t a fire lit in all this great house, & though it is August I am awfully cold. I think I shall never be warm again! I think I shall never be calm again. I think I shall never be myself, I look about me at my own room & see nothing in it that is mine. There is the smell of the flowers in Mrs Brink’s garden, & the perfumes on her mother’s table, & the polish on the wood, the colours of the carpet, the cigarettes I rolled for Peter, the shine on the jewels in the jewel-box, the sight of my own white face in the glass, but it all seems strange to me. I wish I might close my eyes & open them & be at Bethnal Green again, with my own aunty in her own wooden chair. I would rather even be in my room at Mr Vincy’s hotel, with the plain brick wall outside my window. I would rather be there a 100 times than be here where I am now. It is so late, they have put out the lamps at the Crystal Palace. I can see only the great black shape of it against the sky. Now I can hear the sound of the policeman’s voice, & Mrs Silvester is shouting & making Madeleine cry. Mrs Brink’s bedroom is the only quiet place in all the house, & I know that she is lying in it, quite alone in the darkness. I know that she is lying very still & straight with her hair let down & a blanket about her. She might be listening to the shouts & weepings, she might still be wishing she could open her mouth & speak. I know what she would say, if she could do that. I know it so well, I think I can hear it. Her quiet voice, that only I can hear, is the most frightening voice of them all. Part One 24 September 1874 Pa used to say that any piece of history might be made into a tale: it was only a question of deciding where the tale began, and where it ended. That, he said, was all his skill. And perhaps, after all, the histories he dealt with were rather easy to sift like that, to divide up and classify—the great lives, the great works, each one of them neat and gleaming and complete, like metal letters in a box of type. I wish that Pa was with me now. I would ask him how he would start to write the story I have embarked upon to-day. I would ask him how he would neatly tell the story of a prison—of Millbank Prison—which has so many separate lives in it, and is so curious a shape, and must be approached, so darkly, through so many gates and twisting passages. Would he start it with the building of the gaols themselves? I cannot do that, for though I was told the date of it this morning I have forgotten it now; besides which, Millbank is so solid and so antique, I can’t believe that there was ever a time when it did not sit upon that dreary spot beside the Thames, casting its shadow on the black earth there. He might begin it, then, with Mr Shillitoe’s visit to this house, three weeks ago; or, he might begin it at seven this morning, when Ellis first brought me my grey suit and my coat—no, of course he would not start the story there, with a lady and her servant, and petticoats and loose hair. He would start it, I think, at the gate of Millbank, the point that every visitor must pass when they arrive to make their tour of the gaols. Let me begin my record there, then: I am being greeted by the prison porter, who is marking my name off in some great ledger; now a warder is leading me through a narrow arch, and I am about to step across the grounds towards the prison proper— Before I can do that, however, I am obliged to pause a little to fuss with my skirts, which are plain, but wide, and have caught upon some piece of jutting iron or brick. I daresay Pa would not have bothered with the detail of the skirts; I will, however, for it is in lifting my eyes from my sweeping hem that I first see the pentagons of Millbank—and the nearness of them, and the suddenness of that gaze, makes them seem terrible. I look at them, and feel my heart beat hard, and I am afraid. I had a plan of Millbank’s buildings from Mr Shillitoe a week ago, and have had it pinned, since then, on the wall beside this desk. The prison, drawn in outline, has a curious kind of charm to it, the pentagons appearing as petals on a geometric flower—or, as I have sometimes thought, they are like the coloured zones on the chequer-boards we used to paint when we were children. Seen close, of course, Millbank is not charming. Its scale is vast, and its lines and angles, when realised in walls and towers of yellow brick and shuttered windows, seem only wrong or perverse. It is as if the prison had been designed by a man in the grip of a nightmare or a madness—or had been made expressly to drive its inmates mad. I think it would certainly drive me mad, if I had to work as a warder there. As it was, I walked flinchingly beside the man who led me, and paused once to glance behind me, then to gaze at the wedge of sky that showed above. The inner gate at Millbank is set at the junction of two of the pentagons and so, to reach it, one must walk along a narrowing slip of gravel, and feel the walls on either side of one advancing, like the clashing rocks of the Bosporous. The shadows there, flung from the jaundiced bricks, are the colour of bruises. The soil in which the walls are set is damp and dark as tobacco. This soil makes the air there very sour; it grew sourer still, as I was shown into the gaol and had the gate made fast behind me. My heart beat even harder then, and continued to thump while I was made to sit in a plain little room, watching warders cross the open door, seeing them frown and murmur. When Mr Shillitoe came to me at last, I took his hand. I said, ‘I am glad to see you! I had begun to worry that the men might take me for a convict just arrived, and lead me to a cell, and leave me there!’ He laughed. There were never confusions like that, he said, at Millbank. We walked together then, into the prison buildings: for he thought it best to take me straight to the female gaol, to the office of the governess or principal matron there, Miss Haxby. We walked, and he explained our route to me, and I tried to match it with my memory of my paper plan; but the organisation of the prison, of course, is so peculiar, I soon grew lost. The pentagons that hold the men, I know we did not enter. We only passed the gates that lead to those gaols from the hexagon-shaped building at the prison’s middle, the building in which they have their store-rooms, and the surgeon’s house, and Mr Shillitoe’s own offices, and the offices of all his clerks, and the infirmaries and chapel. ‘For you see,’ he said to me once, nodding through a window at a set of yellow smoking chimneys he said were fed by the fires of the prison laundry, ‘you see, we are quite a little city here! Quite self-sustaining. We should do very well, I always think, under a siege.’ He spoke rather proudly, but smiled at his own pride; and I smiled when he did. But if I had grown fearful, having the light and air shut out behind me at the inner gate, then now, as we passed further into the gaol, and that gate was put behind us at the end of a dim and complicated path I should never be able to retrace alone—now, I grew nervous again. Last week, sorting through the papers in Pa’s study, I came across a volume of the prison drawings of Piranesi, and spent an anxious hour, studying them, thinking of all the dark and terrible scenes I might be confronted with to-day. Of course, there was nothing to match the things I had imagined. We passed only along a succession of neat, whitewashed corridors, and were greeted at the junction of these by warders, in dark prison coats. But, the very neatness and the sameness of the corridors and the men made them troubling: I might have been taken on the same plain route ten times over, I should never have known it. Unnerving, too, is the dreadful clamour of the place. Where the warders stand there are gates, that must be unfastened, and swung on grinding hinges, and slammed and bolted; and the empty passages, of course, echo with the sounds of other gates, and other locks and bolts, distant and near. The prison seems caught, in consequence, at the heart of some perpetual private storm, that left my ears ringing. We walked until we reached an antique, studded door that had a wicket in it, which proved to be the entrance to the female gaol. Here we were greeted by a matron, who made Mr Shillitoe a curtsey; and, she being the first woman I had encountered there, I made sure to study her carefully. She was youngish, pale, and quite unsmiling, and dressed in what I was soon to see was the uniform of the place: a grey wool dress, a mantle of black, a grey straw bonnet trimmed with blue, and stout black flat-heeled boots. When she saw me gazing at her she curtseyed again—Mr Shillitoe saying, ‘This is Miss Ridley, our chief matron here’, and then, to her: ‘This is Miss Prior, our new Visitor.’ She walked before us, and there came a steady chink, chink of metal; and I saw then that, like the warders, she wore a wide belt of leather with a buckle of brass and, suspended from the buckle, a chain of polished prison keys. She took us, via more featureless corridors, to a spiral staircase that wound upwards through a tower; it is at the top of the tower, in a bright, white, circular room, filled with windows, that Miss Haxby has her office. ‘You will see the logic of the design of this,’ said Mr Shillitoe as we climbed, growing red and breathless; and of course, I saw it at once, for the tower is set at the centre of the pentagon yards, so that the view from it is all of the walls and barred windows that make up the interior face of the women’s building. The room is very plain. Its floor is bare. There is a rope hung out between two posts, where prisoners, when they are taken there, are obliged to stand, and beyond the rope is a desk. Here, sitting writing in a great black book, we found Miss Haxby herself—‘the Argus of the gaol’, as Mr Shillitoe called her, smiling. When she saw us she rose, took off her spectacles and, like Miss Ridley, made a curtsey. She is a very small lady, and her hair is perfectly white. Her eyes are sharp eyes. Behind her desk, screwed tight to the limewashed bricks, there is set an enamel tablet bearing a piece of dark text:Thou hast set our misdeeds before Thee, and our secret sins in the light of Thy confidence. It was impossible, on entering that room, not to long to walk at once to one of its curving windows and gaze at the view beyond it, and when Mr Shillitoe saw me looking he said, ‘Yes, Miss Prior, come closer to the glass.’ I spent a moment then, studying the wedge-shaped yards below, then looking harder at the ugly prison walls that faced us, and at the banks of squinting windows with which they are filled. Mr Shillitoe said, Now, was that not a very marvellous and terrible sight? There was all the female gaol before me; and behind each of those windows was a single cell, with a prisoner in it. He turned to Miss Haxby. ‘How many women have you on your wards, just now?’ She answered, that there were two hundred and seventy. ‘Two hundred and seventy!’ he said, shaking his head. ‘Will you take a moment, Miss Prior, to imagine those poor women, and all the dark and crooked paths through which they have made their way to Millbank? They might have been thieves, they might have been prostitutes, they might have been brutalised by vice; they will certainly be ignorant of shame, and duty, and all the finer feelings—yes, you may be sure of it. Villainous women, society has deemed them; and society has passed them on, to Miss Haxby and to me, to take close care of them . . .’ But what, he asked me, was the proper way for them to do that? ‘We give them habits that are regular. We teach them their prayers; we teach them modesty. Yet, of necessity, they must spend the great part of their days alone, with their cell walls about them. And there they are—’ he nodded again to the windows before us ‘—perhaps for three years, perhaps for six or seven. There they are: shut up, and brooding. Their tongues we still, their hands we may keep busy; but their hearts, Miss Prior, their wretched memories, their own low thoughts, their mean ambitions—these, we cannot guard. Can we, Miss Haxby?’ ‘No, sir,’ she answered. I said, And yet, he thought a Visitor might do much good with them? He knew it, he said. He was certain of it. Those poor unguarded hearts, they were like children’s hearts, or savages’—they were impressible, they wanted only a finer mould, to shape them. ‘Our matrons might do this,’ he said; ‘our matrons’ hours, however, are long, and their duties hard. The women are sometimes bitter with them, and sometimes rough. But, let a lady go to them, Miss Prior, let a lady do that; let them only know that she has left her comfortable life, solely to visit them, to take an interest in their mean histories. Let them see the miserable contrast between her speech, her manners, and their own poor ways, and they will grow meek, they will grow softened and subdued—I have seen it happen! Miss Haxby has seen it! It is a matter of influence, of sympathies, of susceptibilities tamed . . .’ So he went on. He had said much of this before, of course, downstairs, in our own drawing-room; and there, with Mother frowning, and the clock upon the mantel giving its slow tut-tut, it had sounded very well. You must have been sadly idle, Miss Prior, he had said to me then, since your poor father’s death. He only called to take a set of books that Pa had once had from him; he didn’t know that I had not been idle, but ill. I was glad he did not know it, then. Now, however, with those bleak prison walls before me, and with Miss Haxby gazing at me, and Miss Ridley at the door, her arms across her breast and her chain of keys swinging—now I felt more fearful than ever. For a moment I wished only that they might see the weakness in me, and send me home—as Mother has sent me home sometimes when I have grown anxious at a theatre, thinking I should be ill and have to cry out while the hall was so still. They did not see it. Mr Shillitoe talked on, about Millbank’s history, about its routines, its staff and its visitors. I stood and nodded at his words; sometimes Miss Haxby also nodded. And then, after a time, there sounded a bell, from some part of the prison buildings; and hearing that, Mr Shillitoe and the matrons all made a similar movement, and Mr Shillitoe said that he had spoken longer than he had meant to. That bell was the signal that sent the prisoners to the yards; now he must leave me to the matrons’ care—he said I must be sure to go to him another time, and tell him how the women seem to me. He took my hand, but when I made to walk with him towards the desk he said, ‘No, no, you must stand a little longer there. Miss Haxby, will you come to the window and watch with Miss Prior? Now, Miss Prior, keep your eyes before you, and you shall see something!’ The matron held the door for him, and he was swallowed by the gloom of the tower staircase. Miss Haxby had drawn near, and now we turned to the glass, Miss Ridley stepping to another window to gaze from that. Below us stretched the three earth yards, each separated from its neighbour by a high brick wall that ran, like the spoke on a cart-wheel, from the governess’s tower. Above us hung the dirty city sky, that was streaked with sunlight. ‘A fair day, for September,’ said Miss Haxby. Then she gazed again at the scene below us; and I gazed with her, and waited. For a time, all was still: for the yards there, like the grounds, are desperately bleak, all dirt and gravel—there is not so much as a blade of grass to be shivered by the breezes, or a worm or a beetle for a bird to swoop for. But after perhaps a minute or so I caught a movement in the corner of one of the yards, and then a similar movement in the others. It was the opening of doors, and the emergence of the women; and I don’t think I ever saw such a queer and impressive sight as they made then, for we watched them from our high window and they looked small—they might have been dolls upon a clock, or beads on trailing threads. They spilled into the yards and formed three great elliptical loops, and within a second of their doing that, I could not have said which was the first prisoner to have entered the ground, and which the last, for the loops were seamless, and the women all dressed quite alike, in frocks of brown and caps of white, and with pale blue kerchiefs knotted at their throats. It was only from their poses that I caught the humanity of them: for though they all walked at the same dull pace, there were some, I saw, with drooping heads, and some that limped; some with bodies stiff and hugged against the sudden chill, a few poor souls with faces lifted to the sky—and one, I think, who even raised her eyes to the window that we stood at, and gazed blankly at us. There were all the women of the gaol there, almost three hundred of them, ninety women to each great wheeling line. And in the corner of the yards stood a pair of dark-cloaked matrons, who must stand and watch the prisoners until the exercise is complete. Miss Haxby, I thought, gazed at the plodding women with a kind of satisfaction. ‘See how they know their places,’ she said. ‘There must be kept a certain distance, look, between each prisoner.’ If that distance is breached, the offending woman is reported and loses privileges. If there are women who are old or sick or feeble, or if there are very young girls—‘We have had girls in the past—haven’t we, Miss Ridley?—of twelve and thirteen’—then the matron sets them walking in a circle of their own. ‘How quietly they walk!’ I said. She told me then that the women must keep silent, in all parts of the prison; that they are forbidden to speak, to whistle, to sing, hum ‘or make any kind of voluntary noise’ unless at the express request of a matron or Visitor. ‘And how long must they walk for?’ I asked her then.—They must walk for an hour. ‘And if it should rain?’—If it should rain, the exercise must be forfeited. Those were bad days for the matrons, she said, for then the long confinement made the women ‘fidget and turn saucy’. As she spoke she peered harder at the prisoners: one of the loops had begun to slow, and now turned out of sequence with the circles in the other yards. She said, ‘There is’—and here she named some woman—‘making the pace of her line grow slack. Be sure to speak with her, Miss Ridley, when you make your round.’ I thought it marvellous that she could tell one woman from another; when I told her that, however, she smiled. She said, that she had seen the prisoners walking the yards every day of their terms there, ‘and I have been seven years as principal at Millbank, and before that was chief matron here’—before that, she told me, she was ordinary matron, at the prison at Brixton. All in all, she said, she had spent twenty-one years in gaol; which was a longer sentence than many convicts serve. And yet, there were women walking down there, too, who would outsuffer her. She had seen them come; she dared to say she would not be there to see them leave . . . I asked if such women didn’t make her work the easier, since they must know the habits of the gaol so well? She nodded. ‘Oh yes.’ Then: ‘Is that not true, Miss Ridley? We prefer a longer-server, do we not?’ ‘We do,’ answered the matron. ‘We like the longer-servers, with the one offence behind them—that is,’ she said to me, ‘your poisoners, your vitriol-throwers, your child-murderers, that the magistrates have turned kind on and kept from the rope. Had we a gaolful of such women, we might send our matrons home and let the convicts lock themselves up. It is the petty regulars, the thieves and prostitutes and counterfeiters, that vex us most—and they are devils, miss! Bred to mischief, most of them, and look for nothing better. If they know our habits, they know only what they can get away with, know what tricks will trouble us the most. Devils!’ Her manner stayed very mild, through all this speech; but her words made me blink. Perhaps it was only the association of the chain of keys—which still swung, and sometimes tumbled unmusically together, on the chain of her belt—but her voice seemed to me to be tainted with steel. It was like a bolt in its cradle: I imagine she might draw it back, harsh or gently; I am sure she could never make it soft. I looked at her for a second, then turned again to Miss Haxby. She had only nodded at the matron’s words, and now she almost smiled. ‘You may see,’ she said, ‘how sentimental my matrons grow over their charges!’ She kept her sharp eyes upon me. ‘Do you think us harsh, Miss Prior?’ she asked after a moment. She said I would, of course, form my own opinion of the characters of her women. Mr Shillitoe had asked me to be Visitor to them, and she was grateful to him, and I was to pass my time with them as I thought proper. But she must say to me, as she would say to any lady or gentleman who came to walk her wards: ‘Take care’—she gave the words a dreadful emphasis—‘Take care, in your dealings with Millbank’s women!’ She said I must take care, for example, of my possessions. Many of her girls were pickpockets in their former lives, and if I were to place a watch or a handkerchief in their way, then I would tempt them into their old habits: she asks me therefore not to place such items in their way, just as I would ‘keep my rings and trinkets hidden from the eyes of a servant, so as not to worry her with the prospect of the taking of them’. She said, too, that I must take care in how I speak to the women. I must tell them nothing of the world beyond the prison walls, nothing of what happens in it, not even so much as a notice from a newspaper—especially not that, she said, indeed, ‘for newspapers are forbidden here’. She said I might find a woman seeking me out as an intimate, a counsellor; and if she does that, then I must counsel her ‘as her matron would—that is, in thinking shamefully on her crime, and in making her future life a better one’. But I must make no woman any kind of promises while she is kept in the gaol; nor must I carry objects or information between a woman and her family or friends outside. ‘If a prisoner were to tell you that her mother was ill and about to die,’ she said; ‘if she were to cut off a lock of her hair and plead with you to take it, as a token, to the dying woman, you must refuse it. For take it, Miss Prior, and the prisoner will have you in her power. She will hold the knowledge against you, and use it to make all manner of mischief.’ She said there had been one or two notorious cases like that, in her time at Millbank, that had ended very miserably for all concerned . . . Those, I think, were all her cautions. I thanked her for them—though, all the time she spoke, I found myself terribly mindful of the smooth-faced silent matron who stood nearby: it was like thanking Mother for some piece of hard counsel, while Ellis took the plates away. I gazed again at the circling women, saying nothing, thinking my own thoughts. ‘You like to look at them,’ Miss Haxby said then. She said she had never had a visitor yet that didn’t like to stand at that window and watch the women walk. It was as curative, she thought, as gazing at fish in a tank. After that, I moved from the glass. I think we talked a little longer, about the routines of the gaol; but soon she looked at her watch and said Miss Ridley might now take me on my first tour of the wards. ‘I am sorry I cannot show you them myself,’ she said. ‘But look here,’—nodding to the great dark volume on her desk—‘here is my work for the morning. This is the prisoners’ Character Book, that I must fill with all the reports my matrons make me.’ She drew on her spectacles, and her sharp eyes grew sharper. ‘I shall see now, Miss Prior,’ she said, ‘how good our women have been this week—and how wicked!’ Miss Ridley led me from her, down the shady tower staircase. On the floor below we passed another door. I said, ‘What rooms do you keep here, Miss Ridley?’ She said that those were Miss Haxby’s own apartments, in which she took her dinners and also slept—and I wondered then how it must be, to lie in that quiet tower, with the gaol outside one’s windows, rearing up on every side. I look at the plan beside my desk, and see the tower marked out upon it. I think I see, too, the route Miss Ridley took me on now. She walked very briskly, picking out her unswerving way through those monotonous passages—quite like a compass needle, continually swinging north. There are three miles’ worth of such passages across the prison as a whole, she told me; but when I asked her, were the corridors not very difficult to tell apart?, she snorted. She said that when women come to Millbank to be matrons, they put their heads upon their pillows in the night and seem to be walking, walking, walking down the same white corridor. ‘That happens for a week,’ she said. ‘After that, the matron knows her way all right. After a year, she wishes she might grow lost again, for the novelty.’ She herself has been matron there longer even than Miss Haxby. She could be blinded, she said, and still perform her duties. Here she smiled, but very sourly. Her cheek is white and even, like lard or wax, and her eyes are pale, with heavy lash-less lids. Her hands, I noticed, are kept very clean and smooth—I should say she takes a pumice-stone to them. Her nails are clipped neatly, quite to the quick. She didn’t speak to me again until we reached the wards—that is, until we arrived at a set of bars, which admitted us to a long, chill, silent, cloister-like passage, that held the cells. This passage was, I think, about six feet wide. There was sand upon the floor of it and, upon the walls and ceiling, more lime-wash. High on the left—too high even for me to gaze from—there was a row of windows, barred and thickly glassed; and all along the opposite wall were doorways: doorway after doorway after doorway, all just the same, like the dark, identical doorways one sometimes has to choose between in terrible dreams. The doorways let a little light into the passage, but also something of an odour. The odour—I had caught it at once, in the outer corridors, and I smell it even now, as I write this!—it is vague, but terrible. It is the stifled reek of what they call there ‘nuisance-buckets’, and the lingering exhalations I suppose of many ill-washed mouths and limbs. This was the first ward, Ward A, Miss Ridley told me. There are six wards altogether—two to each floor. Ward A houses the newest set of women, that they term Third Class. She led me then into the first of the empty cells, gesturing as she did so to the two doors fixed at the mouth of it. One of these was of wood, with bolts upon it; the other was an iron gate, with a lock. They keep the gates fastened during the days, and have the wooden doors thrown back: ‘That lets us see the women as we walk,’ said Miss Ridley, ‘and keeps the air of the cells less foul.’ As she spoke, she pushed both doors closed, and the room at once grew darker and seemed to shrink. She put her hands upon her hips, and gazed about her. These were very decent cells, she said: good-sized, and ‘built quite solid’, with a double layer of brick between them. ‘That stops a woman from calling to her neighbour . . .’ I turned away from her. The cell, though dim, was white and very harsh upon the eye, and so bare that, if I close my own eyes now, I find I see again all that was in it, very clearly. There was a single small high window, made of wire and yellow glass—this was one of the windows, of course, that I had gazed at with Mr Shillitoe from Miss Haxby’s tower. Beside the door was an enamel plaque bearing a list of ‘Notices to Convicts’ and a ‘Convicts’ Prayer’. Upon a bare wood shelf there was a mug, a trencher, a box of salt, a Bible and a religious book: The Prisoner’s Companion. There was a chair and table and a folded hammock and, beside the hammock, a tray of canvas sacks and scarlet threads, and a ‘nuisance-bucket’ with a chipped enamel lid. Upon the narrow window-sill there was a prison comb, its ancient teeth worn down or splintered, and snagged with curling hairs and crumbs of scalp. The comb, it turned out, was all there was to distinguish that cell from the ones about it. The women may keep nothing with them of their own, and what they are issued with—the mugs and plates and Bibles—must be kept very neat, and laid out in line with a prison pattern. Walking the length of the ground-floor wards with Miss Ridley, gazing in at all those bleak and featureless chambers, was very miserable; I found I was made giddy, too, by the geometry of the place. For the wards, of course, follow the pentagon’s exterior walls, and are queerly segmented: each time we arrived at the end of one white and monotonous passage, it was to find ourselves at the beginning of another just the same, only stretching off at an unnatural angle. Where two corridors meet there is a spiral staircase. At the junction of the wards there is a tower, where the matron of each floor has a little chamber of her own. All the time we walked there came, from beyond the windows of the cells, the steady tramp, tramp of the women in the prison yards. Now, as we reached the furthest arm of the second ground-floor ward, I heard another ringing of the prison bell, that made the marching rhythm slow, then grow uneven; and after a moment there came the banging of a door, the rattling of bars, and then the sound of boots again, crunching on sand this time, and echoing. I looked at Miss Ridley. ‘Here come the women,’ she said, without excitement; and we stood and listened as the sound grew loud, then louder, then louder still. It seemed, at last, impossibly loud—for we of course had turned three angles of the floor and, though the women were near, we could not see them. I said, ‘They might be ghosts!’—I remembered how there are said to be legions of Roman soldiers that can be heard passing, sometimes, through the cellars of the houses of the City. I think the grounds at Millbank might echo like that, in the centuries when the prison no longer stands there. But Miss Ridley had turned to me. ‘Ghosts!’ she said, studying me queerly. And as she spoke, the prisoners turned the angle of the ward; and then they were suddenly terribly real—not ghosts, not dolls or beads on a string, as they had seemed before, but coarse-faced, slouching women and girls. Their heads went up when they saw us standing there, and when they recognised Miss Ridley their expressions grew meek. Me, however, they seemed to study quite frankly. They looked, but went neatly to their cells, and then sat. And behind them came their matron, locking the gates on them. This matron’s name, I think, is Miss Manning. ‘Miss Prior is making her first visit here,’ Miss Ridley said to her, and the matron nodded, saying, they had been told to expect me. She smiled. I had taken on a pretty task, she said, calling on their girls! And should I like to speak with one of them now?—I said I might as well. She led me to a cell she had not fastened yet, and beckoned to the woman that had entered it. ‘Here, Pilling,’ she said. ‘Here is the new Lady Visitor, come to take a bit of interest in you. Up, and let her see you. Come on, look slippy!’ The prisoner came to me and made a curtsey. Her cheek was flushed and her lip slightly gleaming from her brisk circling of the yard. Miss Manning said, ‘Say who you are and why you are here’, and the woman said at once—though stumbling slightly, over the pronunciation of it—‘Susan Pilling, m’m. Here for thieving.’ Miss Manning showed me then an enamel tablet that hung from a chain beside the entrance to the cell: this gave the woman’s prison number and class, her crime, and the date she was due to be released. I said, ‘How long have you been at Millbank, Pilling?’—She told me, seven months. I nodded. And what age was she? I thought she might be two or three years short of forty. She said, however, that she was twenty-two; and I hesitated at that, then nodded again. How, I asked next, did she care for the life there? She replied that she liked it well enough; and that Miss Manning was kind to her. I said, ‘I am sure she is.’ Then there was a silence. I saw the woman gazing at me, and think the matrons also had their eyes upon me. I thought suddenly of Mother, scolding me when I was two-and-twenty, saying I must talk more when we went calling. I must ask the ladies after the health of their children; or after the pleasant places they had visited; or the work they had painted or sewn. I might admire the cut of a lady’s gown . . . I looked at Susan Pilling’s mud-brown dress; and then I said, how did she like the costume she must wear? What was it—was it serge, or linsey? Here Miss Ridley stepped forward, and caught hold of the skirt and lifted it a little. The gown was of linsey, she said. The stockings—these were blue with a crimson stripe, and very coarse—were of wool. There was one under-skirt of flannel, and another of serge. The shoes, I could see, were stout ones: the men made those, she told me, in the prison shop. The woman stood stiff as a mannequin as the matron counted off these items, and I felt myself obliged to stoop to a fold in her frock and pinch it. It smelt—well, it smelt as a linsey frock would smell when worn all day, in such a place, by one perspiring woman; so that what I next asked was, how often were the dresses changed?—They are changed, the matrons told me, once a month. The petticoats, under-vests and stockings they change once a fortnight. ‘And how often are you allowed to bathe?’ I asked the prisoner herself. ‘We are allowed it, m’m, as often as we like; only, not exceeding two times every month.’ I saw then that her hands, which she kept before her, were pocked with scars; and I wondered how often she was used to bathing, before they sent her to Millbank. I wondered, too, what in the world we would discuss, if I was put in a cell with her and left alone. What I said, however, was: ‘Well, perhaps I will visit you again, and you can tell me more about how you pass your days here. Should you like that?’ She should like it very much, she said promptly. Then: did I mean to tell them stories, from the Scripture? Miss Ridley told me then that there is another Lady Visitor who comes on Wednesdays, who reads the Bible to the women and later questions them upon the text. I told Pilling that, no, I would not read to them, but only listen to them and perhaps hear their stories. She looked at me then, and said nothing. Miss Manning stepped forward, and sent her back into her cell and locked the gate. When we left that ward it was to climb another winding staircase to the next floor, to Wards D and E. Here they keep the women of the penal class, the troublesome women or incorrigibles, who have made mischief at Millbank or been passed on or returned from other institutions for making mischief there. In these wards, all the doors are bolted up; the passage-ways, in consequence, are rather darker than the ones below, and the air is more rank. The matron of this floor is a stout, heavy-browed woman named—of all names!—Mrs Pretty. She walked ahead of Miss Ridley and me and, with a sort of dull relish, like the curator of a wax museum, paused before the cell doors of the worst or most interesting characters to tell me of their crimes, such as— ‘Jane Hoy, ma’am: child-murderer. Vicious as a needle. ‘Phœbe Jacobs: thief. Set fire to her cell. ‘Deborah Griffiths: pickpocket. Here for spitting at the chaplain. ‘Jane Samson: suicide—’ ‘Suicide,’ I said. Mrs Pretty blinked. ‘Took laudanum,’ she said. ‘Took it seven times, and the last time a policeman saved her. They sent her here, as being a nuisance to the public good.’ I heard that, and stood gazing at the shut door, saying nothing. After a moment the matron tilted her head. ‘You are thinking,’ she said confidentially, ‘how do we know she ain’t in there now, with her hands at her own throat?’—though I was not, of course, thinking that. ‘Look here,’ she went on. She showed me how, at the side of each gate, there is a vertical iron flap which can be opened any time the matron pleases, and the prisoner viewed: they call this the ‘inspection’; the women term it the eye. I leaned to look at it, and then moved closer; when Mrs Pretty saw me do that, however, she checked me, saying that she oughtn’t to let me put my face to it. The women were that cunning, she said, and they had had matrons blinded in the past. ‘One girl worked at her supper-spoon until the wood was sharp and—’ I blinked, and stepped hurriedly back. But then she smiled, and gently pressed the flap of iron open. ‘I daresay Samson shan’t harm you,’ she said. ‘You might just take a peep, if you are careful . . .’ This room had iron louvres across its window and so was darker than the cells below, and instead of a hammock it had a hard wood bed. On this the woman—Jane Samson—was seated, her fingers plucking at a shallow basket that she had placed across her lap, that was heaped with coir. She had unpicked perhaps a quarter of the bundle; and there was another, larger, basket of the stuff beside the bed, for her to work on later. A bit of sun struggled through the bars across her window. Its beams were so clotted with brown fibre and with swirling particles of dust, she might, I thought, have been a character in a fairy-tale—a princess, humbled, set to work at some impossible labour at the bottom of a pond. She looked up once as I observed her, then blinked, and rubbed at her eyes where the coir-dust prickled them; and then I let the inspection close, and stepped away. I had begun to wonder, after all, whether she might not try to gesture to me, or call out. I had Miss Ridley take me away from that ward then, and we climbed to the third and highest floor there and met its matron. She proved to be a dark-eyed, kind-faced, earnest woman named Mrs Jelf. ‘Have you come to look at my poor charges?’ she said to me, when Miss Ridley took me to her. Her prisoners are mainly what are termed there Second Class, First Class and Star Class women: they are permitted to have their doors fixed open as they work, like the women on Wards A and B; but their work is easier, they sit knitting stockings or sewing shirts, and they are allowed scissors and needles and pins—this is considered, there, a great gesture of trust. Their cells, when I saw them, had the morning sun in them, and so were very bright and almost cheerful. Their occupants rose and curtseyed when we passed by them, and again seemed to study me very frankly. At last I realised that, just as I looked for the details of their hair and frocks and bonnets, so they looked for the particulars of mine. I suppose that even a gown in mourning colours is a novel one, at Millbank. Many of the prisoners on this ward are those long-servers about whom Miss Haxby had spoken so well. Mrs Jelf now also praised them, saying they were the quietest women in the gaol. Most, she said, would go on from there, before their time, to Fulham Prison, where the routines were a little lighter. ‘They are like lambs to us, aren’t they, Miss Ridley?’ Miss Ridley agreed that they were not like some of the trash they kept on C and D. ‘They are not. We have one here—killed her husband, that was cruel to her—as nicely-bred a woman as you could ever hope to meet.’ The matron nodded into a cell, where a lean-faced prisoner sat patiently teasing at a tangled ball of yarn. ‘Why, we have had ladies here,’ she went on. ‘Ladies, miss, quite like yourself.’ I smiled to hear her say it, and we walked further. Then, from the mouth of a cell a little way along the line there came a thin cry: ‘Miss Ridley? Oh, is that Miss Ridley there?’ A woman was at her gate, her face pressed between the bars. ‘Oh, Miss Ridley mum, have you spoke in my behalf yet, before Miss Haxby?’ We drew closer to her, and Miss Ridley stepped to the gate and struck it with her ring of keys, so that the iron rattled and the prisoner drew back. ‘Will you keep silence?’ said the matron. ‘Do you think I don’t have duties enough, do you think Miss Haxby don’t have business enough, that I must carry your tales to her?’ ‘It is only, mum,’ said the woman, speaking very quickly and stumbling over the words, ‘only that you said you would speak. And when Miss Haxby came this morning she was kept half her time by Jarvis, and would not see me. And my brother has brought his evidence before the courts, and wants Miss Haxby’s word—’ Miss Ridley struck the gate again, and again the prisoner flinched. Mrs Jelf murmured to me: ‘Here is a woman who will pester any matron that passes her cell. She is after an early release, poor thing; I should say, however, that she will be here a few years yet.—Well Sykes, will you let Miss Ridley pass?—I should step a little further down the ward, Miss Prior, or she will try and draw you into her scheme.—Now Sykes, will you be good and do your work?’ Sykes, however, still pressed her case, and Miss Ridley stood chiding her, Mrs Jelf looking on, shaking her head. I moved away, along the ward. The woman’s thin petitions, the matron’s scolds, were made sharp and strange by the acoustics of the gaol; every prisoner I passed had raised her head to catch them—though, when they saw me in the ward beyond their gates, they lowered their gazes and returned to their sewing. Their eyes, I thought, were terribly dull. Their faces were pale, and their necks, and their wrists and fingers, very slender. I thought of Mr Shillitoe saying that a prisoner’s heart was weak, impressionable, and needed a finer mould to shape it. I thought of it, and became aware again of my own heart beating. I imagined how it would be to have that heart drawn from me, and one of those women’s coarse organs pressed into the slippery cavity left at my breast . . . I put my hand to my throat then and felt, before my pulsing heart, my locket; and then my step grew a little slower. I walked until I reached the arch that marked the angle of the ward, then moved a little way beyond it—just far enough to put the matrons from my view, but not enough to t

Amazon

Amazon  Barnes & Noble

Barnes & Noble  Bookshop.org

Bookshop.org  转换文件

转换文件 更多搜索结果

更多搜索结果 其他特权

其他特权